|

Please click on the link to the PDF version of this letter (which allows you to fill in your name and the names of your elected officials) to send to them! Your elected officials need to hear IN NUMBERS that the public hearing on July 24th must be postponed! Dear Queens Local, State, and Federal Elected Officials, We are a coalition of everyday transit riders who elevate the voices of underserved and disadvantaged community members in our pursuit of true equity, accessibility, safety, and sustainability in New York’s public transit. As you may know, the Queens Bus Network Redesign is an historic undertaking envisioned by former New York City Transit President Andy Byford to address a bus system that has become outdated. Thus far, three versions of the Queens Bus Network Redesign have been released. Every Queens City Council member objected to Version 1. The MTA delayed the release of Version 2 (the New Draft Plan), saying they wanted to “get it right this time.” After Version 3 (the Proposed Final Plan), the MTA promised that the thousands of public comments received would be incorporated into a new Final Plan that would be released in the future. Instead, the MTA has done a sudden 360, now proposing a public hearing on the Proposed Final Plan for July 24th, 2024. This hearing must be postponed until at least January 2025 for the following reasons:

As an elected official, we are depending on you to advocate for the needs of your constituents who deserve better transportation options and proper representation by insisting that this public hearing be delayed. Holding the hearing on July 24th would be no different than giving the MTA a blank check to make whatever changes it desires. Rushing the Queens Bus Network Redesign without properly incorporating public input nor performing due diligence would be catastrophic for the riding public, and we must not let that happen. Thank you very much for listening. Sincerely yours, Charlton D’souza, President Jack Nierenberg, Vice President Allan Rosen, Board Member on behalf of the Passengers United team

0 Comments

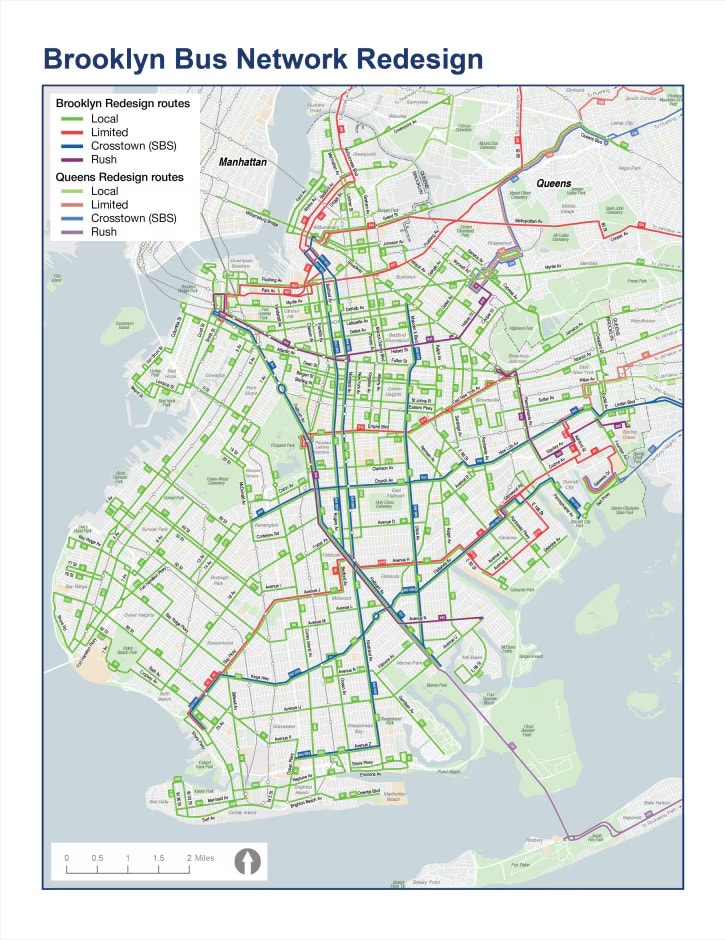

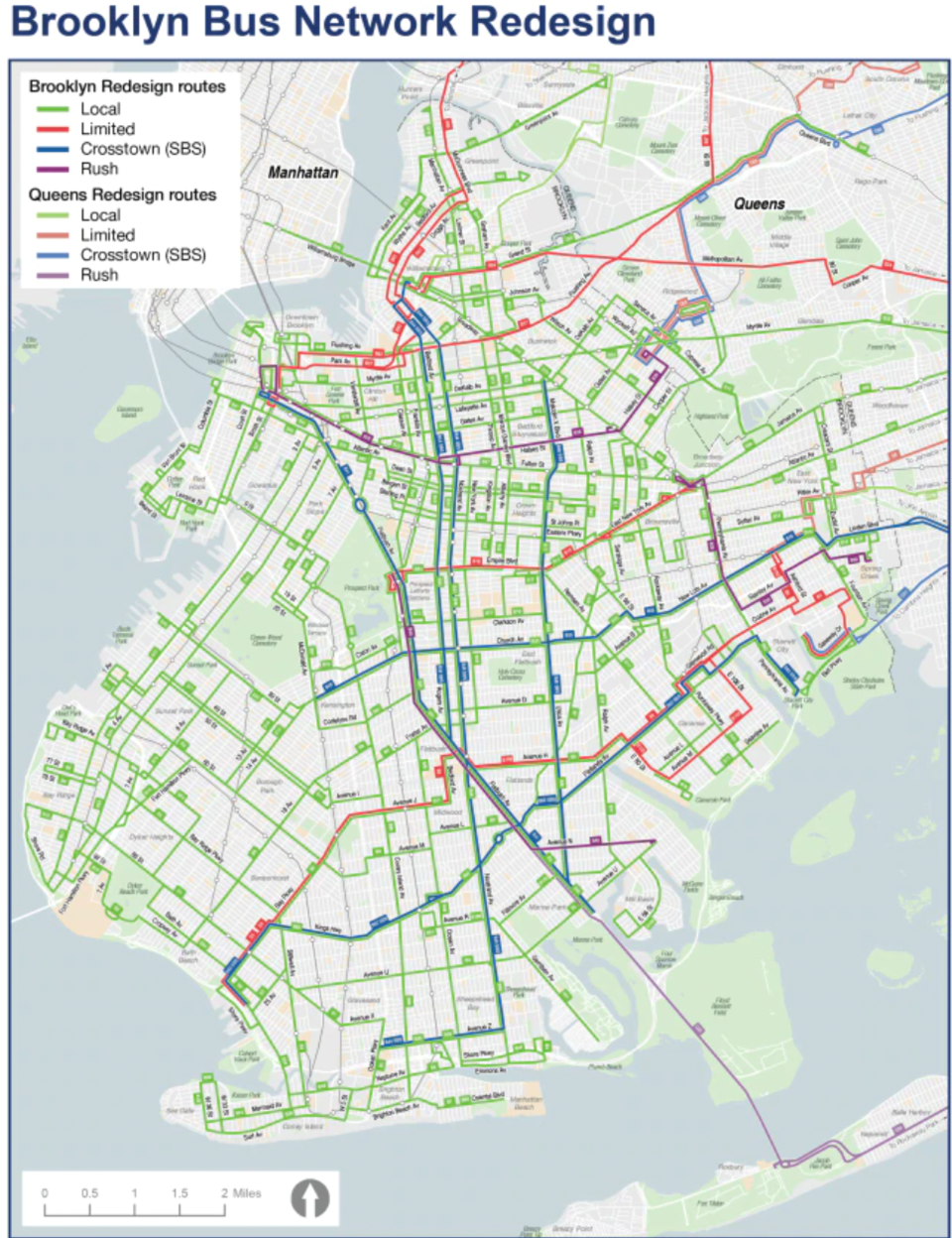

On May 2, 2024, Allan Rosen, former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning who now serves on Passengers United's Board of Directors, spoke about the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign at a meeting by Our Communities Count, a coalition of grassroots groups, at the Emmanuel Baptist Church in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Good Evening. I have been retired from the MTA for nearly 19 years and do not represent the MTA and am not speaking on their behalf. It is imperative we have a bus system that is both efficient and effective in transporting people. Unfortunately, that is not the case today. There are many service gaps, also known as transportation deserts, and bus routes that are outdated or indirect requiring unnecessary transfers and extra fares.

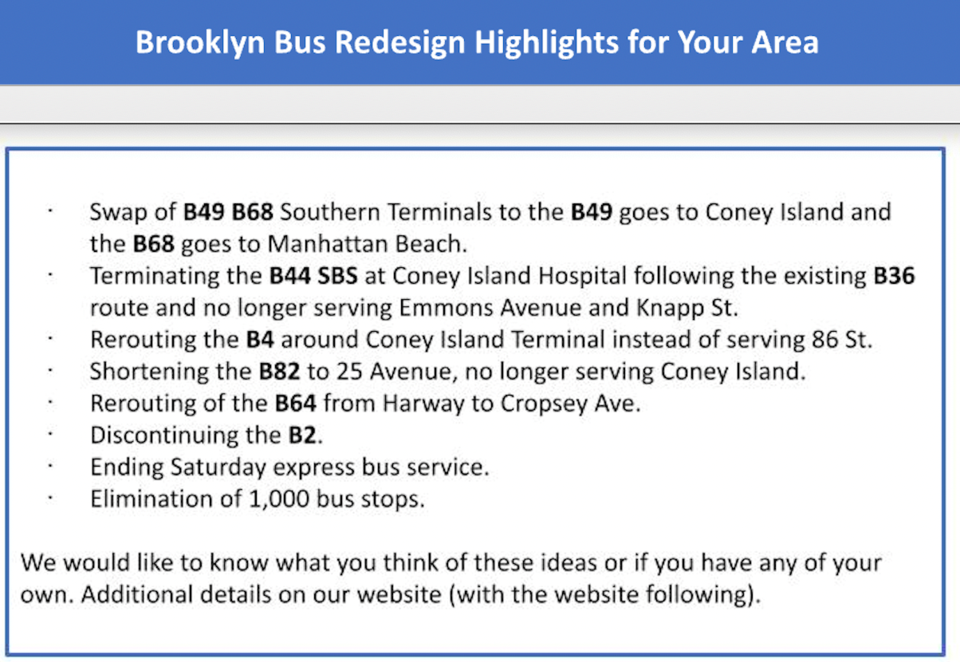

Service reliability is also a big problem and sometimes you feel like you are playing Russian Roulette. Some days the system works fine; other days you seem to wait forever. The MTA recognizes all this. So after years of mostly incremental changes they have undertaken a necessary redesign of the entire bus network throughout the city, by borough. They are now finalizing Queens and produced the first draft for Brooklyn which has received very negative criticism, as did the first draft for Queens. They claim they are trying to make the system better. Unfortunately, they are very misguided which I will explain. Their goals are not our goals as passengers. They are mainly concerned with what the system costs to operate and care less about how passengers are served. Rather than caring about how long your trip takes, they are instead obsessed with bus speeds. Also, the redesigns are not filling service gaps. I know something about buses because I spent my entire career, over three decades, fighting for better bus service after getting my Masters from Columbia in Urban Planning and the last ten years writing about it. In 1981 and 1982, I briefly directed the MTA’s first attempt at updating the Brooklyn bus network to reflect the needs of its passengers. I was also Director of Bus Planning for the MTA. Previously, I was responsible for changing almost a dozen bus routes in Southern Brooklyn in 1978, including the B1 which is now one of the most successful routes in the borough. I worked for the Department of City Planning at that time, and in fact the MTA had to be sued to make those changes because the MTA never had interest on their own to improve the bus system for their passengers. The MTA’s only interest is to ensure public safety and to keep costs manageable, probably by reducing them. That doesn’t mean no one at the MTA doesn’t want to do the right thing. They just are not in positions where they have the power to improve the bus system. The MTA’s supposed outreach for the redesign is merely a charade to give the appearance of public involvement. The purpose of this involvement is to remove the most objectionable parts of their plan to make it politically palatable for the plan to come to fruition, and giving the illusion they are making the system more passenger friendly. You should still make comments on their website regarding what you think of their plan. How do we know public involvement is a charade? For one thing, although the initial Brooklyn plan was released over 15 months ago, there have not been any notices on the buses before or after the release of this plan to alert passengers. The exception was one week when handouts were placed in the take one containers on the buses notifying passengers of a website to go to for further information. Who would even know to look there? When, after three years, the MTA finally decided to announce the Queens Network Redesign on the digital displays on Brooklyn buses, they just as easily could have mentioned the ongoing Brooklyn study, but decided not to. The result is that anyone without computer access has been completely left out of the process and that is mostly seniors who use buses a lot and are affected the most. Their Zoom meetings attracted only 20 to 50 people at each session which were broken into groups of ten to limit the discussion that everyone could hear. Their so called pop-up sessions consisted of two employees wearing buttons saying “Ask me about the Bus Redesign” hiding in subway stations away from heavily trafficked areas. The MTA and most elected officials refuse to hold open forums such as this one where one can freely discuss the proposals. I called each one multiple times, asking them to hold such a forum. The MTA outreach has reached less than one hundredth of one percent of the bus riders. When they do publicize the study a week before the public hearing probably in 2026, it will be too late to make any changes. The time to act is now. The worst feature of the plan is the removal of one third of the bus stops, over 1,000 of them in Brooklyn alone, which is why I started a petition on Change.org, which now has nearly 3,200 signatures. In order to obfuscate the changes, the MTA doesn’t mention the number of stops to be eliminated. You have to count them up individually. Nor do they tell you the walk to the closest bus could be as far as 3/4 of a mile. They don’t even call it bus stop elimination or removal, but bus stop balancing, just to confuse you. Are bus stops unbalanced today?

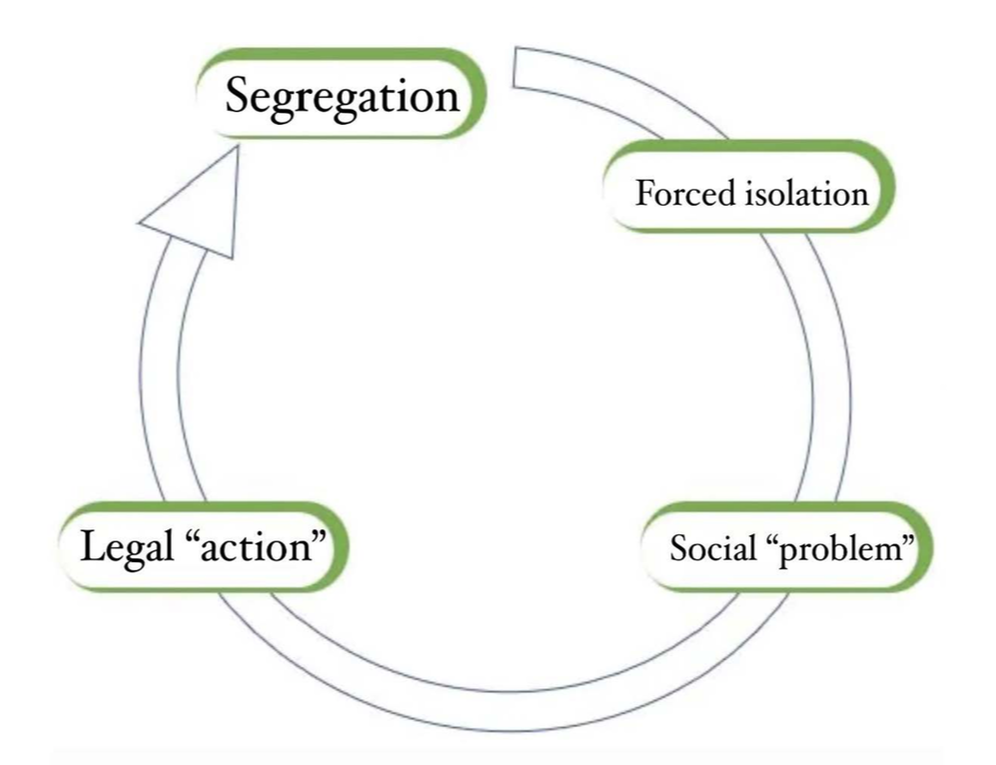

To get all this information from the MTA website, you would have to sift through 400 pages. There are no summaries of the proposals by neighborhood to make the plan more understandable. Although some parts of the borough will receive increases in service, this area isn’t one of them. I don’t see a single improvement here as well as for the area I live in, only longer walks and longer trips. The MTA document, available only on the internet, is intentionally misleading and doesn’t explain the reasons for any of the proposed changes or why alternative plans were eliminated. Nowhere do they talk about disadvantages. Everything that is written is disguised as an improvement. The plan implies the MTA knows what’s best for you because they are the experts. Nowhere do they even show how trips will be quicker or if you will need fewer connections. The opposite is usually true. They need to show how their plan helps more than it hurts, which they fail to do. If the MTA really knows what is best, why are they undoing many of their changes of the last 25 years? They are keeping the bulk of the changes I had made nearly 50 years ago. The first misconception the MTA perpetuates is that buses are slow and eliminating bus stops and adding bus lanes will make them faster. The truth is buses are not slow when compared to cars which average 9 mph on city streets. Brooklyn buses average about 7.2 mph on city streets. It stands to reason that buses have to go a little slower than cars because they must make more stops. So the entire premise for eliminating bus stops is incorrect. Bus lanes are only necessary where bus service is very frequent, not on every street with bus service. The second misconception is the MTA assumes each eliminated bus stop saves 20 seconds on the average. That number is inflated because they fail to consider increased dwell time at the remaining stops and that buses skip infrequently used stops most of the time if no one is getting on or off, and virtually no time is saved by eliminating those bus stops. The MTA only considers acceleration and deceleration in their time savings calculations which are not the only factors. The MTA pretends bus speeds are a problem when the biggest problem is reliability which the redesigns do nothing about. Reliability is improved by increasing supervision, having more buses make shorter trips and reducing double parking mostly by trucks. A handful of supervisors for the entire city cannot guarantee reliability for the MTA’s over 6,000 buses. A state law I proposed to the MTA requiring non-emergency vehicles to give the right-of-way to buses leaving bus stops would save buses more time than eliminating thousands of bus stops which causes unnecessary inconvenience to bus riders. They like the idea, but still want to eliminate bus stops. The accepted domestic walking guideline to a local bus is 1/4 mile. Increasing the distance between bus stops to 1/4 mile, as proposed, flagrantly violates this standard since we know most people do not live at a bus stop or only 1/8 of a mile from one. They usually live up to 1/4 mile from a bus stop. Increasing bus stop spacing increases the present 1/4 mile walk to 1/2 or 3/4 mile at each end of your trip. That is unacceptable, especially for those with mobility problems. The average local bus trip is 2.3 miles. So who would want to walk up to a mile and a half just to ride a bus a little over 2 miles? Few if any. They will make the trip another way or not at all. We shouldn’t be using European bus stop spacing standards as the MTA proposes instead of the US standards we are currently using. The Redesign will result in less ridership causing greater service reductions in the future. After years of research I developed my own plan for Brooklyn that fills service gaps, reduces needed connections, improves reliability and will increase patronage. The MTA refuses to even discuss my plan with me, although I have a successful track record. It is also available on the Passengers United website which I invite you to peruse. If you like it better than the MTA Plan, please let everyone know, especially your elected officials. If eliminating bus stops saves the bus three minutes, but you now have to walk five minutes more, you still have a longer trip, and if the extra walk results in you missing your bus, your trip is now much longer. Nowhere does the MTA even mention passenger trip time. They are only obsessed with bus speeds. So why is the MTA so insistent on eliminating so many bus stops? It’s to reduce the pay hours of its bus drivers, not to help the passengers. The MTA has refused to divulge if the Redesign results in an increase or decrease to revenue hours and miles so we could determine if the redesign results in overall service increases or decreases. In Queens, they claim to be spending an additional $30 million per year in operating costs. They want you to assume this means added service. However using data available through open source, it has been determined that revenue hours are being decreased in Queens. So what the extra $30 million really means is that service will now be more inefficient with more buses traveling to and from depots without passengers. Is this what we want for Brooklyn? Or do we want better service? It is imperative that we let our elected officials know we will not be fooled by the MTA’s charade to improve bus service. We cannot let the MTA destroy our bus system by believing buses operate more efficiently without passengers than with them because without passengers, they can make the trip quicker, and I have that in writing from the MTA. I also suggest you join Passengers United, the only organization representing bus riders fighting for improved mass transit. Riders Alliance, Transportation Alternatives, the PCAC, and others, are all in bed with the MTA and support the MTA’s proposed changes. Also, check out my Brooklyn Bus Redesign Facebook Group and sign the petition. We have strength in numbers and need to fight for what’s right. By Blossom Kelley New York City’s transportation infrastructure has been in need of change for quite some time. This isn't an issue that is uniquely NYC. In fact, movement and transportation in modern cities are generally considered to be ongoing issues, reflective of both the current political and social climate. Yet in a condensed metropolis like New York, the aforementioned factors become highlighted and magnified under the scope of contradictory and conflicting societal pressures. And within this dilemma, it is important to highlight that transportation changes go beyond the physical realm of trains, tunnels, tolls and bridges. The necessity of infrastructure and the way in which it functions within a city often intermingle with the cultural backdrop or landscape of its home, a dynamic that can be particularly lethal if the cultural backdrop is laced with inequality. Transportation is too broad of a theme to fully encapsulate New York City’s geographic and social complexity. In fact, it can be argued that the development of the subway system in New York City marked a major milestone in the city's transportation history as well as within the larger culture of travel and mobility within the United States. The first underground train system was proposed by Alfred Ely Beach in 1869 and was opened in 1870, consisting of a pneumatic subway that operated for only a short period. However, it was the construction of the city-owned and operated Independent Subway System (IND) in 1932 that truly transformed transportation in New York. The IND expanded on the existing system first opened in 1904. It was originally intended to compete with the private systems and provide a more efficient and accessible mode of transportation for the growing population. This expansion of the subway system greatly expanded travel in and around Midtown and Lower Manhattan, changing the city's landscape and facilitating a revitalized urban growth. The evolution of the metro system in New York City not only shaped the physical infrastructure of the city but also had a significant impact on racial segregation. The transportation system was racially segregated for much of the 19th century. This segregation was eventually challenged and overturned through the efforts of individuals like Elizabeth Jennings, but the impact of transportation on segregation extended beyond the desegregation of public transit. The development of highways, such as America's interstate highway system, often cut through urban neighborhoods, disproportionately affecting minority communities. These transportation decisions played a central role in shaping the development and spatial segregation of cities across America, including New York City. Much like the American Interstate Highway, the Cross Bronx Expressway fundamentally reshaped New York City’s relationship to transportation and segregation. Originally conceived by Robert Moses, the Cross Bronx Expressway was built between 1948 and 1972, and was the first highway that was constructed through a densely populated urban environment in the United States. The need for the expressway arose due to the increasing traffic congestion and the desire for a more efficient transportation route from the isles to the mainland, as the Bronx is the only borough that is geographically connected to the continental United States. Construction on the Cross Bronx Expressway began in 1948, making it the first large-scale urban freeway built in the country. The development of this highway was a complex undertaking, involving the demolition of numerous buildings and the displacement of many residents. The construction process was challenging and required extensive planning to navigate the densely populated areas. The Cross Bronx Expressway had a significant social and environmental impact on the surrounding communities. The expressway acted as a physical barrier, dividing neighborhoods and solidifying cultural and economic differences between the north and the south Bronx. The highway disrupted existing communities, closed local businesses, and increased traffic levels, going against its original intended purpose. The resulting air and noise pollution from the constant flow of vehicles have had detrimental effects on the health of the approximately 220,000 people living near the expressway. Moreover, the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway contributed to the exacerbation of existing racial and socioeconomic disparities between the Bronx and the other boroughs. Even today, the Bronx is the borough most afflicted by poverty, substance abuse and is often considered to be New York’s most forgotten borough. In recent years, the negative impacts of the Cross Bronx Expressway have been given rightful attention and analysis. Many studies have been initiated to evaluate the needs of the communities situated alongside the expressway corridor and to propose solutions to reduce pollution, improve traffic safety, and create new green spaces. The aim is to mitigate the environmental and health consequences of the expressway and to reconnect the fractured neighborhoods that were previously isolated. These initiatives recognize the importance of addressing the social and environmental injustices caused by the construction and operation of the Cross Bronx Expressway but rarely do they highlight the connection shared between the Bronx crossway and its relationship to other tools of exclusion. The implementation of sustainable and community-centered solutions may alleviate certain negative impacts of the expressway, but the affected communities will never be able to thrive in their full capacity because they were structurally designed to be little more than the city’s proverbial dumping ground. Segregation is embedded in the geographical fabric of New York City. Although for many American readers the word ‘segregation’ evokes only the legalized racial segregation rampant in the Southern United States for more than a hundred years, that level of legal segregation is only one of the many possible examples of segregation’s manifestations. Segregation is defined by Oxford Dictionary as “the action or state of setting someone or something apart from others.” Ask any New Yorker, whether freshly indoctrinated or lifelong, and they will tell you that rather than a cohesive union of metropolitan fusion, New York is best thought of as a land mass divided by neighborhoods which closely resemble small towns. The division of land and resources in New York City was often a result of direct placement — where certain ethnic groups were allowed to go, where they were confined to, and which areas they encouraged their loved ones to travel to. It is in these areas that the various congestion problems can be more closely analyzed. For example, the South Bronx — a borough already torn apart by the transportation needs of other city inhabitants — also houses the world-famous Yankee Stadium. Each year, the South Bronx is utterly disrupted by the team's schedule. Road closures, limited parking, motor vehicle accidents are routine for the over 500,000 people that call this area their home. However, the congestion and disruption are not acknowledged by the city. In many ways, the chaos is accepted as a part of the neighborhood, no different than the other structural letdowns handed to its residents by the City of New York. The Yankees’ empire gives little to no solution to the congestion and danger that they place residents in each year. This is in direct contrast to how congestion is viewed and dealt with in Manhattan. As a matter of fact, driving into Midtown Manhattan may now cost as much as $23. Although this decision is labeled as a method to help alleviate congestion, this new toll module is a form of segregation, one of the many ways in which segregation appears in a society. The implementation of the new Midtown toll was allegedly designed to address the issues of traffic congestion and pollution while simultaneously generating revenue to improve the city's mass transit system. By charging drivers to enter Midtown Manhattan, the city highlighted the Midtown toll as the most probable way to reduce traffic and pollution, all while raising $1 billion in annual revenue for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Although the toll zone will primarily cover Midtown Manhattan, the impact of this toll will be felt all over the city. The exact price for the toll zone is yet to be finalized, but the overall goal is to reduce the number of vehicles entering this area and encourage alternative modes of transportation. By implementing this toll, the city hopes to incentivize drivers to consider other options such as public transportation, walking, or cycling, thereby reducing the overall number of vehicles on the road and improving traffic flow. However, the rising MTA prices contradict the message coming from City Hall. Furthermore, the MTA's own Environmental Assessment admits that this "congestion pricing" will worsen air quality in the outer boroughs, especially the Bronx, because of the diversion of traffic from Manhattan to the surrounding areas. The MTA claims that a small fraction of the revenue from this toll will be spent on efforts to mitigate (not eliminate) the increased pollution, which could lead to greater health risks for many. Yet the MTA and many elected officials continue to mislead the public and say that congestion pricing will improve air quality for the city, as elaborated on here. The disconnect between City Hall’s message and the consequences of their policies is no accident. Forcing the city into fragmented versions of itself allows the aforementioned atrocities to go unnoticed in certain communities, perpetuating a feeling of both distrust and unrest that goes beyond transportation policies. The distrust and unrest that is felt throughout the city is operating on top of a historical legacy of rationalized separation, the legal segregation of housing and commercial communities within the city. In general, redlining and housing discrimination played a significant role in perpetuating segregation in New York City. Redlining, a discriminatory housing practice that emerged in the 1930s, involved the systematic denial of mortgage loans and insurance to residents in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The practice was facilitated by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored corporation that drew maps outlining areas deemed too hazardous for investment. Redlining effectively restricted Black Americans and other people of color to specific neighborhoods and limited their access to quality housing and economic opportunities. This discriminatory practice had lasting effects on the spatial segregation of communities in New York City. Forced removal of New York citizens, allowed under the guise of redlining and other methods of “urban renewal” further exacerbated segregation within the city. Urban renewal projects, which initially began in the mid-20th century, aimed to ‘revitalize’ urban areas by demolishing blighted neighborhoods and constructing new developments. However, these projects disproportionately impacted low-income communities, often displacing People of Color and contributing to the destruction of affordable housing. The urban renewal proceedings decimated many Black communities in America, not just in New York City, which led to further segregation and the loss of cultural and social institutions. The combination of redlining and urban renewal created a cycle of segregation that has had lasting impacts on the city's neighborhoods and communities. Much of New York’s cultural atmosphere has changed in the past few decades, as the city’s demographics have shifted. Neighborhoods that were once brought to life by a specific ethnic group are now void of the cultural fluidity that once lined its streets. The price of transportation and its unreliability has continued to rise, causing the displacement of Native New Yorkers as many have found themselves forced to flee their original neighborhoods. Whether the displacement is directly or indirectly forced, its history is still a major aggressor in the circulation and continuation of segregation in contemporary society. This is because segregation works through stages. The final stage or culmination of segregation’s impact is what usually gets discussed in policy rhetoric and informal conversations. The hyper focus on the final stage allows the process behind segregation to almost always remain hidden. As stated previously, segregation works through forced isolation. 39% of the South Bronx’s population is Black. 60% of the South Bronx’s population is Hispanic and/or Latine. Many South Bronx residents chose their home out of financial necessity since, as previously mentioned, the Bronx has the highest rate of poverty in New York City and is home to the poorest congressional district in the United States. The forced isolation of individuals usually results in a social “problem” that requires immediate legal “action”. This legal “action” fuels segregation, it fuels the separation of New York’s population into those who have the freedom to choose and those who are victims of the rapid change and mounting expenses. Suddenly, adding a toll to the portal of Manhattan’s financial and cultural epicenter becomes larger than simple traffic management.

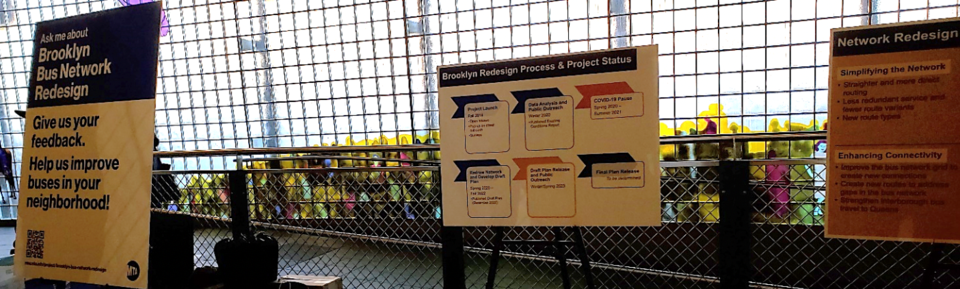

Hiding segregation’s intricate and devastating process from the public allows it to continue churning in plain sight. There are very few ways a social or political process can be stopped if it isn’t fully recognized or understood. It is because of that very reason that one of the “greatest cities in the world” can constantly get away with pushing their residents into underdeveloped squalor, attaching unattainable charges to their transportation and access to resources. When New York City’s relationship to poverty and racial identity is analyzed, the legalized oppression appears even more heinous and intentional. So many people — whether People of Color or working class individuals — are constantly withheld from this city’s alleged greatness despite being the very thing that makes it possible. The continuation of these exclusionary tactics by the MTA and elected officials will further divide New York City, chipping away at its culture and integrity until it is finally depleted for good. Unless, of course, they are finally stopped. Blossom Kelley is a poet and essayist from the Bronx, New York. Her research focuses primarily on the intersection of linguistics and philosophy, analyzing both the neurological basis for language production and acquisition alongside sociological frameworks for defining and understanding modern conceptions of what it means to be ‘human’. Allan Rosen, a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning, shares his thoughts on the latest Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign outreach efforts. By Allan Rosen The MTA completed its five open houses and 13 pop-up sessions (including four MetroCard Mobile Sales events) for the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign on June 9. That was in addition to its 18 virtual meetings earlier this year. These events were poorly publicized, only mentioned on the MTA website and in an occasional news article, TV news story, or an e-mail from an elected official. There were no signs on the buses or digital displays specifically referring to these meetings. There were a few handouts available on buses only with a link to the MTA website, and occasional mention of the Redesign on buses with digital displays, but no mention of any outreach. There have been no real discussions with communities where the MTA justifies its decisions with data and adequately answers questions. At its Pop-Up events, the MTA stationed three personnel in or near subway stations wearing buttons where riders were supposed to approach them with questions about the Redesign. The staff were accompanied by two signs hanging on the wall. However, there were no signs at MetroCard Bus Mobile Events, only three people with buttons saying “Ask Me About the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign.” At the Open Houses, there also was a table, Network Local and Express Bus Maps posted, and signage summarizing general advantages of the plan. Five or more MTA personnel were available to answer questions at those events. They each had a 500-page book with them which was a printout of the information available on their website which was used to answer questions. Attendance was so light, that personnel were able to spend as much as 20 or 30 minutes with each person explaining the plan. The MTA spoke to only about two dozen passengers at each of these events. When I questioned MTA personnel about this, the response was that having meaningful discussions with two dozen people at each event was their goal which they accomplished. Many seniors, who comprise a significant amount of ridership, are not computer literate and were totally left out of the process. Even if a senior without a computer finds out about the Redesign events by word of mouth or an-mail and attends a Pop-Up or an Open House session, there is no way such a complex plan could be understood by anyone just by someone explaining the plan from a book without a handout other than a multi-lingual link to a website. How is a senior without computer access supposed to learn which bus stops are being eliminated when the posted sign only states that bus stop balancing will speed buses? How could someone even know what the euphemism of “bus stop balancing” even means without asking? Are bus stops today off-balance? How is a senior supposed to learn that his or her express bus service will not be operating on Saturdays when that information is not volunteered by the staff and the posted bus map of express bus service available only at the five open houses, mentions nothing about Saturday service being discontinued? How is someone able to understand a complex local Brooklyn Bus Map that is mainly in green, unlike the ones currently in use using multiple colors to distinguish routes? I attended the Sheepshead Bay Pop-Up, the Coney Island Open House and the Mobile Sales MetroCard Pop-Up Event in Sheepshead Bay. Two staff members from Government Relations and one planner were available to answer questions at the first event. There were two large signs only in English announcing the Redesign. They were placed in the corner of the entrance areas by the employee restrooms, away from the foot traffic entering and exiting the station. I insisted that the signs be moved to an area where they would be noticed. They were moved to just outside the station. One sign was placed on an el pillar. That was an improvement, but people entering or exiting on Sheepshead Bay Road still could not see them without first turning their head sideways. As a result, of the 1,000 or 2,000 using the station during the 3 hours of the event, only about 100 saw the signs. About 12 people engaged in conversations with the team. Much of the time, the team was idle. At one point, the planner made a meager attempt to attract riders by asking if anyone uses the bus. Without a megaphone, she could not be heard and was ineffective so she gave up after about a minute; the rest of the time the team just waited to be approached and was virtually ignored. At the conclusion, I was informed that one person from Government Relations spoke to a dozen more people at one of the bus stops when she realized people at the subway station were uninterested in bus changes. The Coney Island Open House was no more effective. For some unknown reason, the subway station was nearly deserted at rush hour. Perhaps it would have been more effective if the event were held instead at the neighboring bus terminal, which is the terminal for three affected bus routes, the B68, B74 and B82. At the bus terminal, there was a small unclear sign directing people to the location where it was being held. The shortest route to the location was to pay your fare and then exit the paid area to reach it. Otherwise, you had to walk at least 600 feet depending on where you entered the station. There was also signage at Surf Avenue saying “Ask us about the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign” and a small arrow once you walked inside directing you to walk further. One person posted on my Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign Facebook site, that she thought the site was unmanned and left, having not walked inside the terminal to see the arrow. If at these 15 events, the goal of speaking to 2 dozen riders at each event is achieved, the MTA would have engaged with 400 people. Add that to the 600 different individuals who attended the virtual workshops, for a total of 1,000 people. There are 625,000 daily weekday passengers in Brooklyn. How can reaching less than 0.1% of them be considered “effective” public participation? Yet, the MTA insists that it is. Perhaps, it would be if the .01% were a statistically valid representative sample which it was not. Distributing handouts summarizing key changes in the specific area targeted, with an understandable map on the reverse, distributed to everyone passing through the station or a neighboring bus stop would have reached a hundred times as many riders, but still would only reach 1% of affected riders. Still better than 0.1%. If these outreach sessions had been advertised on the buses or mentioned more in the newsletters, on TV and e-mails from all elected officials, that percentage of passengers reached would have greatly increased. A flyer for the Sheepshead Bay Station could have looked something like this with the addition of the MTA logo: What would have been so difficult for the MTA to print and distribute this? However, the MTA chose not to explain its plan in terms that could be easily understood. They do not want you to realize they are truncating and discontinuing bus routes and shortening service spans or eliminating 2,300 bus stops in Brooklyn and Queens. They would rather use terms such as “bus stop balancing” to speed service to obfuscate what they are really doing. They only tell you where service is discontinued or which bus stops will be removed if you specifically ask them about it. They are refusing to provide any support or back-up materials showing how they arrived at their decisions, even after being asked repeatedly for this. They will only answer questions if the answer is already contained on their website, offering no additional information. They are not being accountable or transparent. I already raised all these issues with a high-level MTA official through ongoing correspondence in the past few months after he approached me following my testimony in January at the MTA Board Meeting. Here are some quotes from his responses: “Our outreach has evolved in the pandemic era to best suit our customers’ needs and provide a welcoming environment…I appreciate your feedback on our process but will ask you to understand it’ll be different than what you’re asking for yet effective…The unfortunate reality is we will not see eye to eye on what is effective, or practicable, when it comes to outreach. We fundamentally believe our process is working. We have established a track record of success in prior redesigns and we look forward to continuing it in Brooklyn and Queens…No one suggested .01% is the goal, you did. I have responded to the vast majority of what you have asked of me…We are transparent and accountable to our riders and stakeholders. We are not however required to do as you personally suggest at every turn. Have a nice rest of your day.” However, on the bright side, I was successful in getting the MTA to investigate and support a state law requiring non-emergency vehicles to give the right-of-way to buses leaving bus stops as a way for buses to move faster as I have been suggesting for about five years. They will try to get the legislation introduced, but even if passed, they do not view it as a substitute for not eliminating massive numbers of bus stops which they still intend to do. It is unfortunate they are ignoring the 3,060 people who have signed thus far signed the petition against massive bus stop removal giving at least a thousand reasons. The FutureBus passengers who have read the plan must tell the MTA what they like and dislike. They should suggest better ideas for the MTA to consider in a setting where everyone in attendance can hear them, rather than only submitting their ideas privately. Our state and local elected officials must insist on well-publicized public town halls in their districts to accomplish this. The MTA must provide reasons why alternate ideas are unacceptable. A single public hearing ten days before changes take effect as required by law is grossly insufficient. My sources tell me that the Brooklyn Borough President has no interest in holding a borough-wide town hall or Borough Board Community Meeting where the MTA can be put on the spot and be required to provide the back-up data requested. Data such as (1) how many daily B15 bus riders will now require a transfer to reach JFK Airport who currently have a direct trip after the B15 is truncated? (2) How removing lightly utilized bus stops increasing walking distances to some routes up to ¾ of a mile violating all accepted domestic standards, helps passengers by reducing their trip times? (3) How truncating routes such as the B69 increasing waiting times by 15 minutes or more by requiring extra transfers, helps passengers? (4) How many will be negatively affected by truncations such as with the B69 and B103 as compared to the numbers who are expected to be better served with new routes such as the B55? Twenty years ago, the MTA insisted they had a computer model that could simulate the numbers being helped and hurt by testing different sets of new bus route proposals and comparing the results. What happened to it? Surely in twenty years it has improved or has it never worked the way it was intended and is unusable? As a public agency, why should the MTA be immune from answering such questions? The MTA’s line now is “Don’t worry, it’s only a draft” so you shouldn’t take the proposals seriously. After the most objectionable parts are removed and the final plan goes into effect, the new line will be “Don’t worry, we will continue to adjust routes and service levels on an ongoing basis as ridership and usage warrants.” Realistically, the chances of restoring a truncated or eliminated route are slim. Two from the MTA told me they were upset with me for being too critical about the MTA. I do give the MTA credit when I feel they deserve it which is not often. One claimed to have read my 100-page bus route and service plan, which is more comprehensive than theirs and solves more problems such as filling service gaps in transit deserts and straightens more routes such as the B16. However, she told me, “Your problem is that you don’t want to see any changes.” That type of statement undermines any credibility the MTA might have. The MTA also has refused to have any discussions with me regarding my plan which took me years to develop, although I was responsible for the current B1 route, one of the most successful and well-utilized routes in the borough. Is this how the MTA is listening? We cannot allow the MTA to trim our bus service without adequate justification to save operating expenses while calling the redesign an improvement and labeling it a success, as they most certainly will do. Anyone who has read my plan must let the MTA know which features from it should be included in their plan. The future of the Brooklyn Bus Network is now in the hands of our state and local elected officials. Allan Rosen is a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning with three decades of experience in transportation and a Master's Degree in Urban Planning. On Twitter @BrooklynBus. This article was originally featured in BKReader on July 19, 2023.

Republished with permission from the author. ATTENTION BROOKLYN AND QUEENS LIRR COMMUTERS: Atlantic Ticket is slated to be eliminated! This not only includes the $5 one-way ticket between Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn and stations in Queens, but also the $60 weekly ticket which includes a 7-Day Unlimited MetroCard for easy and affordable subway and bus connections!

Instead, there would be a CityTicket that costs $5 during off-peak hours and $7 during peak hours (a $2 increase from Atlantic Ticket's flat rate). However, this ticket does not include any free subway or bus transfers! This also comes after the MTA chose to significantly reduce through-service to/from Atlantic Terminal, which has resulted in a reduction in ridership on the line. To then eliminate Atlantic Ticket and strip away all its benefits from riders who now get third-class service on the line would be despicable and discriminatory against Brooklyn and Queens community members, many of whom are unable to afford the $7 CityTicket and would be adversely affected. These important discounts must not only be saved, but expanded so that all of us can afford easier and more accessible public transit options. For example, they should be included at Grand Central, which would be another incentive to take public transportation and fill up the empty trains that run to/from this new Manhattan terminal. New York City's affordability crisis shows that discounts for public transit, especially for those who need it the most, are critical now. By Jack Nierenberg, Vice President After testing the demo turnstiles and speaking with officials from the manufacturers, I can report that I am impressed with what I saw. New fare gate technology is long overdue for the MTA, and it was great to get a sense of what transit riders could be using in the near future. Whichever option is ultimately settled on, it will be a game changer for the MTA, the city, and the region.

Our discussions covered many facets of the new technology, and my findings are promising. First, these turnstiles will feature design elements and computerized systems (such as cameras and sensors) that would help deter fare evasion, improve accessibility, and allow for quick and easy maintenance. Inevitable defects and/or vandalism are addressed by redundancy in the computerized systems and the durability of the design. For example, the arms, which are made of shatterproof plexiglass, can be easily replaced. We also addressed the issue of accessibility, on which the width of the gates has a bearing. If a gate is too narrow, it is less accessible, and it is crucial that everyone is able to easily pass through them. There will, of course, be wider gates for those with strollers or mobility devices. Cameras and/or sensors would also be able to effectively determine how long to keep the gate open based on factors such as their position, articles, etc. I am also hopeful that, by their design intended to prevent fare evasion by incentive, these new turnstiles would help improve safety in the subway system. The issue of safety is a very complex one, and while this won’t solve it 100%, it is one smaller (but still substantial) piece of the puzzle. Additionally, the versatility of these new turnstiles could enable OMNY to be rolled out on the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North, and I am glad that the MTA seems open to exploring that possibility. This could transform fare collection on the railroads into a tap-in/tap-out system similar to that in the Netherlands (which I was very impressed with when I used it). Such a system would allow for easier, more flexible commuting by train (especially since conductors would not need to check tickets anymore), as well as streamlined transferring between transit modes. Of course, this would be at the MTA’s discretion, but I encourage them to consider such a course of action. With that said, the questions that remain are: 1) How much will this cost, and 2) where will the funds come from? While the answer is unclear at the moment, we implore the MTA to make sure that the cost is not borne by everyday New Yorkers and especially those in marginalized and/or vulnerable demographic groups. As long as that is fulfilled, we are all for the new turnstiles! |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed