|

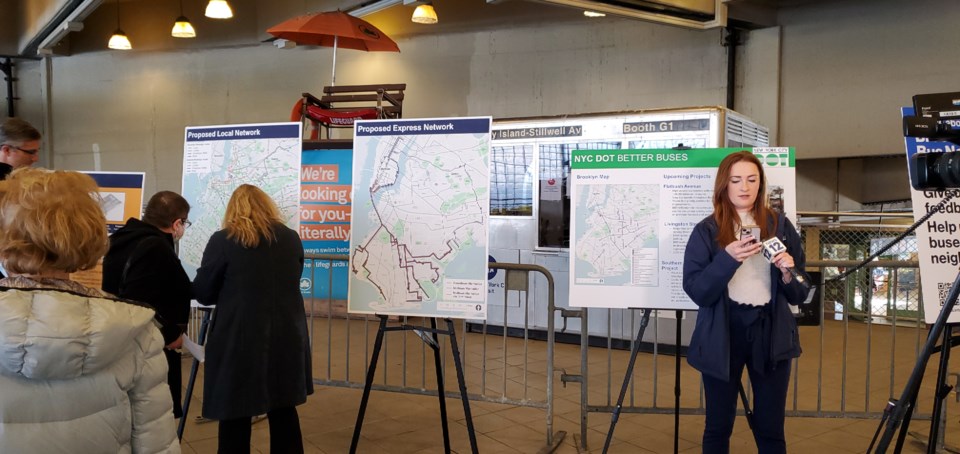

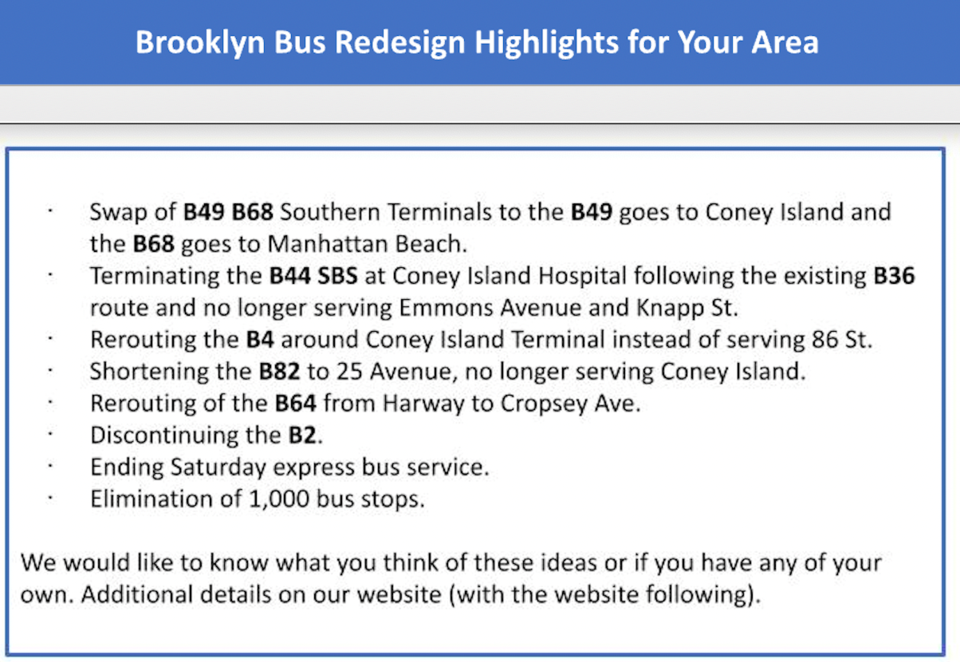

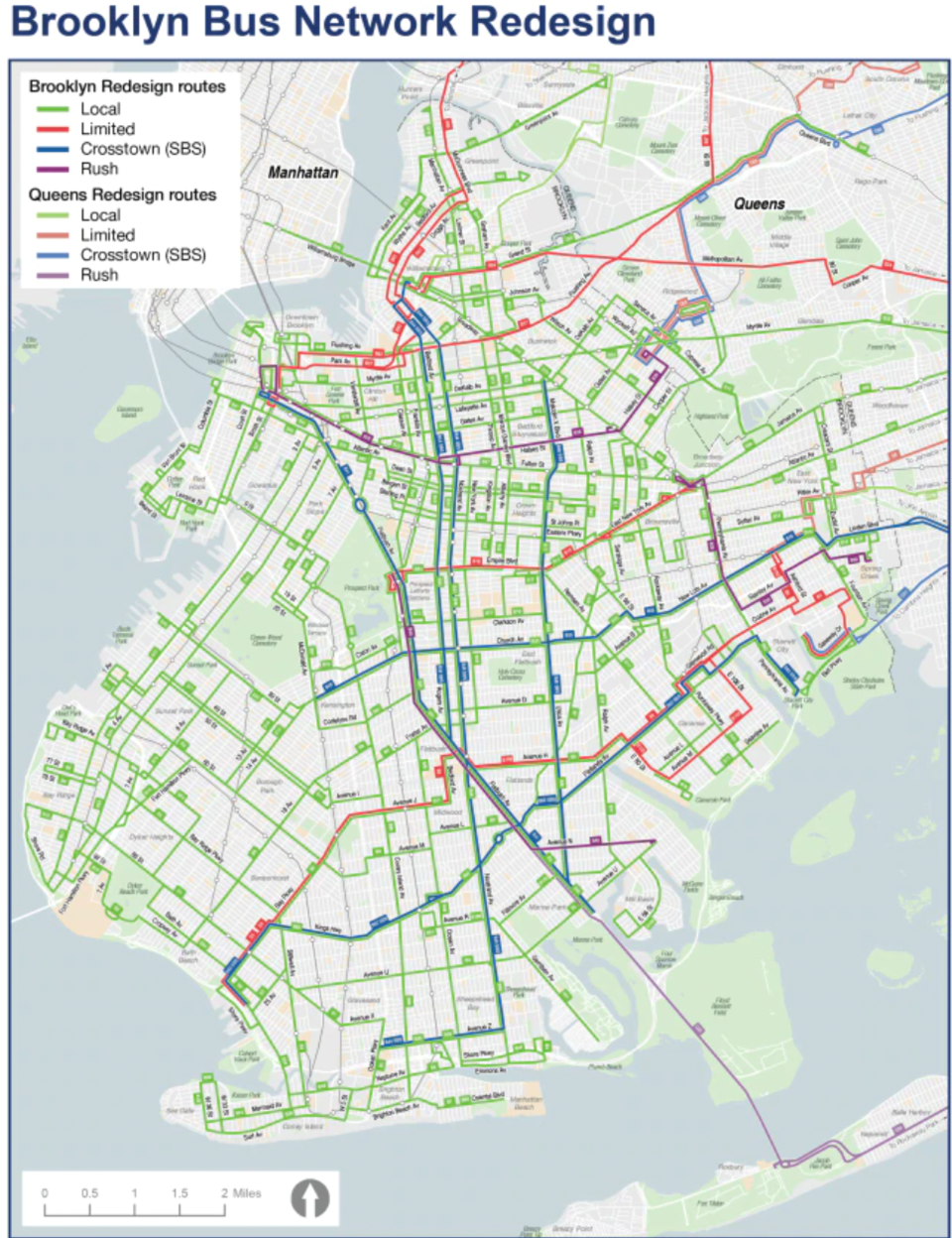

Allan Rosen, a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning, shares his thoughts on the latest Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign outreach efforts. By Allan Rosen The MTA completed its five open houses and 13 pop-up sessions (including four MetroCard Mobile Sales events) for the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign on June 9. That was in addition to its 18 virtual meetings earlier this year. These events were poorly publicized, only mentioned on the MTA website and in an occasional news article, TV news story, or an e-mail from an elected official. There were no signs on the buses or digital displays specifically referring to these meetings. There were a few handouts available on buses only with a link to the MTA website, and occasional mention of the Redesign on buses with digital displays, but no mention of any outreach. There have been no real discussions with communities where the MTA justifies its decisions with data and adequately answers questions. At its Pop-Up events, the MTA stationed three personnel in or near subway stations wearing buttons where riders were supposed to approach them with questions about the Redesign. The staff were accompanied by two signs hanging on the wall. However, there were no signs at MetroCard Bus Mobile Events, only three people with buttons saying “Ask Me About the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign.” At the Open Houses, there also was a table, Network Local and Express Bus Maps posted, and signage summarizing general advantages of the plan. Five or more MTA personnel were available to answer questions at those events. They each had a 500-page book with them which was a printout of the information available on their website which was used to answer questions. Attendance was so light, that personnel were able to spend as much as 20 or 30 minutes with each person explaining the plan. The MTA spoke to only about two dozen passengers at each of these events. When I questioned MTA personnel about this, the response was that having meaningful discussions with two dozen people at each event was their goal which they accomplished. Many seniors, who comprise a significant amount of ridership, are not computer literate and were totally left out of the process. Even if a senior without a computer finds out about the Redesign events by word of mouth or an-mail and attends a Pop-Up or an Open House session, there is no way such a complex plan could be understood by anyone just by someone explaining the plan from a book without a handout other than a multi-lingual link to a website. How is a senior without computer access supposed to learn which bus stops are being eliminated when the posted sign only states that bus stop balancing will speed buses? How could someone even know what the euphemism of “bus stop balancing” even means without asking? Are bus stops today off-balance? How is a senior supposed to learn that his or her express bus service will not be operating on Saturdays when that information is not volunteered by the staff and the posted bus map of express bus service available only at the five open houses, mentions nothing about Saturday service being discontinued? How is someone able to understand a complex local Brooklyn Bus Map that is mainly in green, unlike the ones currently in use using multiple colors to distinguish routes? I attended the Sheepshead Bay Pop-Up, the Coney Island Open House and the Mobile Sales MetroCard Pop-Up Event in Sheepshead Bay. Two staff members from Government Relations and one planner were available to answer questions at the first event. There were two large signs only in English announcing the Redesign. They were placed in the corner of the entrance areas by the employee restrooms, away from the foot traffic entering and exiting the station. I insisted that the signs be moved to an area where they would be noticed. They were moved to just outside the station. One sign was placed on an el pillar. That was an improvement, but people entering or exiting on Sheepshead Bay Road still could not see them without first turning their head sideways. As a result, of the 1,000 or 2,000 using the station during the 3 hours of the event, only about 100 saw the signs. About 12 people engaged in conversations with the team. Much of the time, the team was idle. At one point, the planner made a meager attempt to attract riders by asking if anyone uses the bus. Without a megaphone, she could not be heard and was ineffective so she gave up after about a minute; the rest of the time the team just waited to be approached and was virtually ignored. At the conclusion, I was informed that one person from Government Relations spoke to a dozen more people at one of the bus stops when she realized people at the subway station were uninterested in bus changes. The Coney Island Open House was no more effective. For some unknown reason, the subway station was nearly deserted at rush hour. Perhaps it would have been more effective if the event were held instead at the neighboring bus terminal, which is the terminal for three affected bus routes, the B68, B74 and B82. At the bus terminal, there was a small unclear sign directing people to the location where it was being held. The shortest route to the location was to pay your fare and then exit the paid area to reach it. Otherwise, you had to walk at least 600 feet depending on where you entered the station. There was also signage at Surf Avenue saying “Ask us about the Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign” and a small arrow once you walked inside directing you to walk further. One person posted on my Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign Facebook site, that she thought the site was unmanned and left, having not walked inside the terminal to see the arrow. If at these 15 events, the goal of speaking to 2 dozen riders at each event is achieved, the MTA would have engaged with 400 people. Add that to the 600 different individuals who attended the virtual workshops, for a total of 1,000 people. There are 625,000 daily weekday passengers in Brooklyn. How can reaching less than 0.1% of them be considered “effective” public participation? Yet, the MTA insists that it is. Perhaps, it would be if the .01% were a statistically valid representative sample which it was not. Distributing handouts summarizing key changes in the specific area targeted, with an understandable map on the reverse, distributed to everyone passing through the station or a neighboring bus stop would have reached a hundred times as many riders, but still would only reach 1% of affected riders. Still better than 0.1%. If these outreach sessions had been advertised on the buses or mentioned more in the newsletters, on TV and e-mails from all elected officials, that percentage of passengers reached would have greatly increased. A flyer for the Sheepshead Bay Station could have looked something like this with the addition of the MTA logo: What would have been so difficult for the MTA to print and distribute this? However, the MTA chose not to explain its plan in terms that could be easily understood. They do not want you to realize they are truncating and discontinuing bus routes and shortening service spans or eliminating 2,300 bus stops in Brooklyn and Queens. They would rather use terms such as “bus stop balancing” to speed service to obfuscate what they are really doing. They only tell you where service is discontinued or which bus stops will be removed if you specifically ask them about it. They are refusing to provide any support or back-up materials showing how they arrived at their decisions, even after being asked repeatedly for this. They will only answer questions if the answer is already contained on their website, offering no additional information. They are not being accountable or transparent. I already raised all these issues with a high-level MTA official through ongoing correspondence in the past few months after he approached me following my testimony in January at the MTA Board Meeting. Here are some quotes from his responses: “Our outreach has evolved in the pandemic era to best suit our customers’ needs and provide a welcoming environment…I appreciate your feedback on our process but will ask you to understand it’ll be different than what you’re asking for yet effective…The unfortunate reality is we will not see eye to eye on what is effective, or practicable, when it comes to outreach. We fundamentally believe our process is working. We have established a track record of success in prior redesigns and we look forward to continuing it in Brooklyn and Queens…No one suggested .01% is the goal, you did. I have responded to the vast majority of what you have asked of me…We are transparent and accountable to our riders and stakeholders. We are not however required to do as you personally suggest at every turn. Have a nice rest of your day.” However, on the bright side, I was successful in getting the MTA to investigate and support a state law requiring non-emergency vehicles to give the right-of-way to buses leaving bus stops as a way for buses to move faster as I have been suggesting for about five years. They will try to get the legislation introduced, but even if passed, they do not view it as a substitute for not eliminating massive numbers of bus stops which they still intend to do. It is unfortunate they are ignoring the 3,060 people who have signed thus far signed the petition against massive bus stop removal giving at least a thousand reasons. The FutureBus passengers who have read the plan must tell the MTA what they like and dislike. They should suggest better ideas for the MTA to consider in a setting where everyone in attendance can hear them, rather than only submitting their ideas privately. Our state and local elected officials must insist on well-publicized public town halls in their districts to accomplish this. The MTA must provide reasons why alternate ideas are unacceptable. A single public hearing ten days before changes take effect as required by law is grossly insufficient. My sources tell me that the Brooklyn Borough President has no interest in holding a borough-wide town hall or Borough Board Community Meeting where the MTA can be put on the spot and be required to provide the back-up data requested. Data such as (1) how many daily B15 bus riders will now require a transfer to reach JFK Airport who currently have a direct trip after the B15 is truncated? (2) How removing lightly utilized bus stops increasing walking distances to some routes up to ¾ of a mile violating all accepted domestic standards, helps passengers by reducing their trip times? (3) How truncating routes such as the B69 increasing waiting times by 15 minutes or more by requiring extra transfers, helps passengers? (4) How many will be negatively affected by truncations such as with the B69 and B103 as compared to the numbers who are expected to be better served with new routes such as the B55? Twenty years ago, the MTA insisted they had a computer model that could simulate the numbers being helped and hurt by testing different sets of new bus route proposals and comparing the results. What happened to it? Surely in twenty years it has improved or has it never worked the way it was intended and is unusable? As a public agency, why should the MTA be immune from answering such questions? The MTA’s line now is “Don’t worry, it’s only a draft” so you shouldn’t take the proposals seriously. After the most objectionable parts are removed and the final plan goes into effect, the new line will be “Don’t worry, we will continue to adjust routes and service levels on an ongoing basis as ridership and usage warrants.” Realistically, the chances of restoring a truncated or eliminated route are slim. Two from the MTA told me they were upset with me for being too critical about the MTA. I do give the MTA credit when I feel they deserve it which is not often. One claimed to have read my 100-page bus route and service plan, which is more comprehensive than theirs and solves more problems such as filling service gaps in transit deserts and straightens more routes such as the B16. However, she told me, “Your problem is that you don’t want to see any changes.” That type of statement undermines any credibility the MTA might have. The MTA also has refused to have any discussions with me regarding my plan which took me years to develop, although I was responsible for the current B1 route, one of the most successful and well-utilized routes in the borough. Is this how the MTA is listening? We cannot allow the MTA to trim our bus service without adequate justification to save operating expenses while calling the redesign an improvement and labeling it a success, as they most certainly will do. Anyone who has read my plan must let the MTA know which features from it should be included in their plan. The future of the Brooklyn Bus Network is now in the hands of our state and local elected officials. Allan Rosen is a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning with three decades of experience in transportation and a Master's Degree in Urban Planning. On Twitter @BrooklynBus. This article was originally featured in BKReader on July 19, 2023.

Republished with permission from the author.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed