|

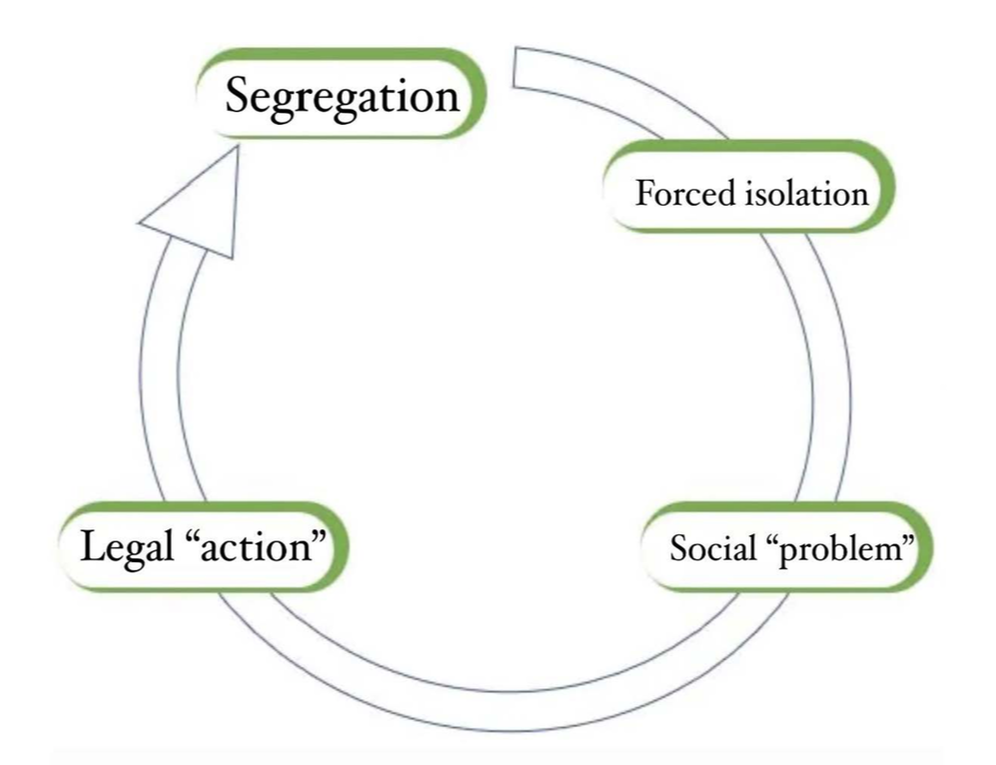

By Blossom Kelley New York City’s transportation infrastructure has been in need of change for quite some time. This isn't an issue that is uniquely NYC. In fact, movement and transportation in modern cities are generally considered to be ongoing issues, reflective of both the current political and social climate. Yet in a condensed metropolis like New York, the aforementioned factors become highlighted and magnified under the scope of contradictory and conflicting societal pressures. And within this dilemma, it is important to highlight that transportation changes go beyond the physical realm of trains, tunnels, tolls and bridges. The necessity of infrastructure and the way in which it functions within a city often intermingle with the cultural backdrop or landscape of its home, a dynamic that can be particularly lethal if the cultural backdrop is laced with inequality. Transportation is too broad of a theme to fully encapsulate New York City’s geographic and social complexity. In fact, it can be argued that the development of the subway system in New York City marked a major milestone in the city's transportation history as well as within the larger culture of travel and mobility within the United States. The first underground train system was proposed by Alfred Ely Beach in 1869 and was opened in 1870, consisting of a pneumatic subway that operated for only a short period. However, it was the construction of the city-owned and operated Independent Subway System (IND) in 1932 that truly transformed transportation in New York. The IND expanded on the existing system first opened in 1904. It was originally intended to compete with the private systems and provide a more efficient and accessible mode of transportation for the growing population. This expansion of the subway system greatly expanded travel in and around Midtown and Lower Manhattan, changing the city's landscape and facilitating a revitalized urban growth. The evolution of the metro system in New York City not only shaped the physical infrastructure of the city but also had a significant impact on racial segregation. The transportation system was racially segregated for much of the 19th century. This segregation was eventually challenged and overturned through the efforts of individuals like Elizabeth Jennings, but the impact of transportation on segregation extended beyond the desegregation of public transit. The development of highways, such as America's interstate highway system, often cut through urban neighborhoods, disproportionately affecting minority communities. These transportation decisions played a central role in shaping the development and spatial segregation of cities across America, including New York City. Much like the American Interstate Highway, the Cross Bronx Expressway fundamentally reshaped New York City’s relationship to transportation and segregation. Originally conceived by Robert Moses, the Cross Bronx Expressway was built between 1948 and 1972, and was the first highway that was constructed through a densely populated urban environment in the United States. The need for the expressway arose due to the increasing traffic congestion and the desire for a more efficient transportation route from the isles to the mainland, as the Bronx is the only borough that is geographically connected to the continental United States. Construction on the Cross Bronx Expressway began in 1948, making it the first large-scale urban freeway built in the country. The development of this highway was a complex undertaking, involving the demolition of numerous buildings and the displacement of many residents. The construction process was challenging and required extensive planning to navigate the densely populated areas. The Cross Bronx Expressway had a significant social and environmental impact on the surrounding communities. The expressway acted as a physical barrier, dividing neighborhoods and solidifying cultural and economic differences between the north and the south Bronx. The highway disrupted existing communities, closed local businesses, and increased traffic levels, going against its original intended purpose. The resulting air and noise pollution from the constant flow of vehicles have had detrimental effects on the health of the approximately 220,000 people living near the expressway. Moreover, the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway contributed to the exacerbation of existing racial and socioeconomic disparities between the Bronx and the other boroughs. Even today, the Bronx is the borough most afflicted by poverty, substance abuse and is often considered to be New York’s most forgotten borough. In recent years, the negative impacts of the Cross Bronx Expressway have been given rightful attention and analysis. Many studies have been initiated to evaluate the needs of the communities situated alongside the expressway corridor and to propose solutions to reduce pollution, improve traffic safety, and create new green spaces. The aim is to mitigate the environmental and health consequences of the expressway and to reconnect the fractured neighborhoods that were previously isolated. These initiatives recognize the importance of addressing the social and environmental injustices caused by the construction and operation of the Cross Bronx Expressway but rarely do they highlight the connection shared between the Bronx crossway and its relationship to other tools of exclusion. The implementation of sustainable and community-centered solutions may alleviate certain negative impacts of the expressway, but the affected communities will never be able to thrive in their full capacity because they were structurally designed to be little more than the city’s proverbial dumping ground. Segregation is embedded in the geographical fabric of New York City. Although for many American readers the word ‘segregation’ evokes only the legalized racial segregation rampant in the Southern United States for more than a hundred years, that level of legal segregation is only one of the many possible examples of segregation’s manifestations. Segregation is defined by Oxford Dictionary as “the action or state of setting someone or something apart from others.” Ask any New Yorker, whether freshly indoctrinated or lifelong, and they will tell you that rather than a cohesive union of metropolitan fusion, New York is best thought of as a land mass divided by neighborhoods which closely resemble small towns. The division of land and resources in New York City was often a result of direct placement — where certain ethnic groups were allowed to go, where they were confined to, and which areas they encouraged their loved ones to travel to. It is in these areas that the various congestion problems can be more closely analyzed. For example, the South Bronx — a borough already torn apart by the transportation needs of other city inhabitants — also houses the world-famous Yankee Stadium. Each year, the South Bronx is utterly disrupted by the team's schedule. Road closures, limited parking, motor vehicle accidents are routine for the over 500,000 people that call this area their home. However, the congestion and disruption are not acknowledged by the city. In many ways, the chaos is accepted as a part of the neighborhood, no different than the other structural letdowns handed to its residents by the City of New York. The Yankees’ empire gives little to no solution to the congestion and danger that they place residents in each year. This is in direct contrast to how congestion is viewed and dealt with in Manhattan. As a matter of fact, driving into Midtown Manhattan may now cost as much as $23. Although this decision is labeled as a method to help alleviate congestion, this new toll module is a form of segregation, one of the many ways in which segregation appears in a society. The implementation of the new Midtown toll was allegedly designed to address the issues of traffic congestion and pollution while simultaneously generating revenue to improve the city's mass transit system. By charging drivers to enter Midtown Manhattan, the city highlighted the Midtown toll as the most probable way to reduce traffic and pollution, all while raising $1 billion in annual revenue for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Although the toll zone will primarily cover Midtown Manhattan, the impact of this toll will be felt all over the city. The exact price for the toll zone is yet to be finalized, but the overall goal is to reduce the number of vehicles entering this area and encourage alternative modes of transportation. By implementing this toll, the city hopes to incentivize drivers to consider other options such as public transportation, walking, or cycling, thereby reducing the overall number of vehicles on the road and improving traffic flow. However, the rising MTA prices contradict the message coming from City Hall. Furthermore, the MTA's own Environmental Assessment admits that this "congestion pricing" will worsen air quality in the outer boroughs, especially the Bronx, because of the diversion of traffic from Manhattan to the surrounding areas. The MTA claims that a small fraction of the revenue from this toll will be spent on efforts to mitigate (not eliminate) the increased pollution, which could lead to greater health risks for many. Yet the MTA and many elected officials continue to mislead the public and say that congestion pricing will improve air quality for the city, as elaborated on here. The disconnect between City Hall’s message and the consequences of their policies is no accident. Forcing the city into fragmented versions of itself allows the aforementioned atrocities to go unnoticed in certain communities, perpetuating a feeling of both distrust and unrest that goes beyond transportation policies. The distrust and unrest that is felt throughout the city is operating on top of a historical legacy of rationalized separation, the legal segregation of housing and commercial communities within the city. In general, redlining and housing discrimination played a significant role in perpetuating segregation in New York City. Redlining, a discriminatory housing practice that emerged in the 1930s, involved the systematic denial of mortgage loans and insurance to residents in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The practice was facilitated by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored corporation that drew maps outlining areas deemed too hazardous for investment. Redlining effectively restricted Black Americans and other people of color to specific neighborhoods and limited their access to quality housing and economic opportunities. This discriminatory practice had lasting effects on the spatial segregation of communities in New York City. Forced removal of New York citizens, allowed under the guise of redlining and other methods of “urban renewal” further exacerbated segregation within the city. Urban renewal projects, which initially began in the mid-20th century, aimed to ‘revitalize’ urban areas by demolishing blighted neighborhoods and constructing new developments. However, these projects disproportionately impacted low-income communities, often displacing People of Color and contributing to the destruction of affordable housing. The urban renewal proceedings decimated many Black communities in America, not just in New York City, which led to further segregation and the loss of cultural and social institutions. The combination of redlining and urban renewal created a cycle of segregation that has had lasting impacts on the city's neighborhoods and communities. Much of New York’s cultural atmosphere has changed in the past few decades, as the city’s demographics have shifted. Neighborhoods that were once brought to life by a specific ethnic group are now void of the cultural fluidity that once lined its streets. The price of transportation and its unreliability has continued to rise, causing the displacement of Native New Yorkers as many have found themselves forced to flee their original neighborhoods. Whether the displacement is directly or indirectly forced, its history is still a major aggressor in the circulation and continuation of segregation in contemporary society. This is because segregation works through stages. The final stage or culmination of segregation’s impact is what usually gets discussed in policy rhetoric and informal conversations. The hyper focus on the final stage allows the process behind segregation to almost always remain hidden. As stated previously, segregation works through forced isolation. 39% of the South Bronx’s population is Black. 60% of the South Bronx’s population is Hispanic and/or Latine. Many South Bronx residents chose their home out of financial necessity since, as previously mentioned, the Bronx has the highest rate of poverty in New York City and is home to the poorest congressional district in the United States. The forced isolation of individuals usually results in a social “problem” that requires immediate legal “action”. This legal “action” fuels segregation, it fuels the separation of New York’s population into those who have the freedom to choose and those who are victims of the rapid change and mounting expenses. Suddenly, adding a toll to the portal of Manhattan’s financial and cultural epicenter becomes larger than simple traffic management.

Hiding segregation’s intricate and devastating process from the public allows it to continue churning in plain sight. There are very few ways a social or political process can be stopped if it isn’t fully recognized or understood. It is because of that very reason that one of the “greatest cities in the world” can constantly get away with pushing their residents into underdeveloped squalor, attaching unattainable charges to their transportation and access to resources. When New York City’s relationship to poverty and racial identity is analyzed, the legalized oppression appears even more heinous and intentional. So many people — whether People of Color or working class individuals — are constantly withheld from this city’s alleged greatness despite being the very thing that makes it possible. The continuation of these exclusionary tactics by the MTA and elected officials will further divide New York City, chipping away at its culture and integrity until it is finally depleted for good. Unless, of course, they are finally stopped. Blossom Kelley is a poet and essayist from the Bronx, New York. Her research focuses primarily on the intersection of linguistics and philosophy, analyzing both the neurological basis for language production and acquisition alongside sociological frameworks for defining and understanding modern conceptions of what it means to be ‘human’.

7 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed